I was working on a script the other day, and it was driving me nuts. It worked, sure, but it was just… slow. Really slow. I had that feeling that this could be so much faster if I could figure out where the hold-up was.

My first thought was to start tweaking things. I could optimise the data loading. Or rewrite that for loop? But I stopped myself. I’ve fallen into that trap before, spending hours “optimising” a piece of code only to find it made barely any difference to the overall runtime. Donald Knuth had a point when he said, “Premature optimisation is the root of all evil.”

I decided to take a more methodical approach. Instead of guessing, I was going to find out for sure. I needed to profile the code to obtain hard data on exactly which functions were consuming the majority of the clock cycles.

In this article, I’ll walk you through the exact process I used. We’ll take a deliberately slow Python script and use two fantastic tools to pinpoint its bottlenecks with surgical precision.

The first of these tools is called cProfile, a powerful profiler built into Python. The other is called snakeviz, a brilliant tool that transforms the profiler’s output into an interactive visual map.

Setting up a development environment

Before we start coding, let’s set up our development environment. The best practice is to create a separate Python environment where you can install any necessary software and experiment, knowing that anything you do won’t impact the rest of your system. I’ll be using conda for this, but you can use any method with which you’re familiar.

#create our test environment

conda create -n profiling_lab python=3.11 -y

# Now activate it

conda activate profiling_labNow that we have our environment set up, we need to install snakeviz for our visualisations and numpy for the example script. cProfile is already included with Python, so there’s nothing more to do there. As we’ll be running our scripts with a Jupyter Notebook, we’ll also install that.

# Install our visualization tool and numpy

pip install snakeviz numpy jupyterNow type in jupyter notebook into your command prompt. You should see a jupyter notebook open in your browser. If that doesn’t happen automatically, you’ll likely see a screenful of information after the jupyter notebook command. Near the bottom of that, there will be a URL that you should copy and paste into your browser to initiate the Jupyter Notebook.

Your URL will be different to mine, but it should look something like this:-

http://127.0.0.1:8888/tree?token=3b9f7bd07b6966b41b68e2350721b2d0b6f388d248cc69daWith our tools ready, it’s time to look at the code we’re going to fix.

Our “Problem” Script

To properly test our profiling tools, we need a script that exhibits clear performance issues. I’ve written a simple program that simulates processing problems with memory, iteration and CPU cycles, making it a perfect candidate for our investigation.

# run_all_systems.py

import time

import math

# ===================================================================

CPU_ITERATIONS = 34552942

STRING_ITERATIONS = 46658100

LOOP_ITERATIONS = 171796964

# ===================================================================

# --- Task 1: A Calibrated CPU-Bound Bottleneck ---

def cpu_heavy_task(iterations):

print(" -> Running CPU-bound task...")

result = 0

for i in range(iterations):

result += math.sin(i) * math.cos(i) + math.sqrt(i)

return result

# --- Task 2: A Calibrated Memory/String Bottleneck ---

def memory_heavy_string_task(iterations):

print(" -> Running Memory/String-bound task...")

report = ""

chunk = "report_item_abcdefg_123456789_"

for i in range(iterations):

report += f"|{chunk}{i}"

return report

# --- Task 3: A Calibrated "Thousand Cuts" Iteration Bottleneck ---

def simulate_tiny_op(n):

pass

def iteration_heavy_task(iterations):

print(" -> Running Iteration-bound task...")

for i in range(iterations):

simulate_tiny_op(i)

return "OK"

# --- Main Orchestrator ---

def run_all_systems():

print("--- Starting FINAL SLOW Balanced Showcase ---")

cpu_result = cpu_heavy_task(iterations=CPU_ITERATIONS)

string_result = memory_heavy_string_task(iterations=STRING_ITERATIONS)

iteration_result = iteration_heavy_task(iterations=LOOP_ITERATIONS)

print("--- FINAL SLOW Balanced Showcase Finished ---")Step 1: Collecting the Data with cProfile

Our first tool, cProfile, is a deterministic profiler built into Python. We can run it from code to execute our script and record detailed statistics about every function call.

import cProfile, pstats, io

pr = cProfile.Profile()

pr.enable()

# Run the function you want to profile

run_all_systems()

pr.disable()

# Dump stats to a string and print the top 10 by cumulative time

s = io.StringIO()

ps = pstats.Stats(pr, stream=s).sort_stats("cumtime")

ps.print_stats(10)

print(s.getvalue())Here is the output.

--- Starting FINAL SLOW Balanced Showcase ---

-> Running CPU-bound task...

-> Running Memory/String-bound task...

-> Running Iteration-bound task...

--- FINAL SLOW Balanced Showcase Finished ---

275455984 function calls in 30.497 seconds

Ordered by: cumulative time

List reduced from 47 to 10 due to restriction <10>

ncalls tottime percall cumtime percall filename:lineno(function)

2 0.000 0.000 30.520 15.260 /home/tom/.local/lib/python3.10/site-packages/IPython/core/interactiveshell.py:3541(run_code)

2 0.000 0.000 30.520 15.260 {built-in method builtins.exec}

1 0.000 0.000 30.497 30.497 /tmp/ipykernel_173802/1743829582.py:41(run_all_systems)

1 9.652 9.652 14.394 14.394 /tmp/ipykernel_173802/1743829582.py:34(iteration_heavy_task)

1 7.232 7.232 12.211 12.211 /tmp/ipykernel_173802/1743829582.py:14(cpu_heavy_task)

171796964 4.742 0.000 4.742 0.000 /tmp/ipykernel_173802/1743829582.py:31(simulate_tiny_op)

1 3.891 3.891 3.892 3.892 /tmp/ipykernel_173802/1743829582.py:22(memory_heavy_string_task)

34552942 1.888 0.000 1.888 0.000 {built-in method math.sin}

34552942 1.820 0.000 1.820 0.000 {built-in method math.cos}

34552942 1.271 0.000 1.271 0.000 {built-in method math.sqrt}We have a bunch of numbers that can be difficult to interpret. This is where snakeviz comes into its own.

Step 2: Visualising the bottleneck with snakeviz

This is where the magic happens. Snakeviz takes the output of our profiling file and converts it into an interactive, browser-based chart, making it easier to find bottlenecks.

So let’s use that tool to visualise what we have. As I’m using a Jupyter Notebook, we need to load it first.

%load_ext snakevizAnd we run it like this.

%%snakeviz

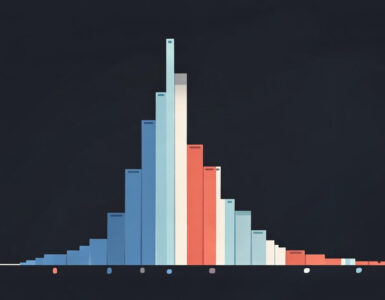

main()The output comes in two parts. First is a visualisation like this.

What you see is a top-down “icicle” chart. From the top to the bottom, it represents the call hierarchy.

At the very top: Python is executing our script (

Next: the script’s __main__ execution (

The memory-intensive processing part isn’t labelled on the chart. That’s because the proportion of time associated with this task is much smaller than the times apportioned to the other two intensive functions. As a result, we see a much smaller, unlabelled block to the right of the cpu_heavy_task block.

Note that, for analysis, there is also a Snakeviz chart style called a Sunburst chart. It looks a bit like a pie chart except it contains a set of increasingly large concentric circles and arcs. The idea beng that the time taken by functions to run is represented by the angular extent of the arc size of the circle. The root function is a circle in the middle of viz. The root function runs by calling the sub-functions below it and so on. We wont be looking at that display type in this article.

Visual confirmation, like this, can be so much more impactful than staring at a table of numbers. I didn’t need to guess anymore where to look; the data was staring me right in the face.

The visualisation is quickly followed by a block of text detailing the timings for various parts of your code, much like the output of the cprofile tool. I’m only showing the first dozen or so lines of this, as there were 30+ in total.

ncalls tottime percall cumtime percall filename:lineno(function)

----------------------------------------------------------------

1 9.581 9.581 14.3 14.3 1062495604.py:34(iteration_heavy_task)

1 7.868 7.868 12.92 12.92 1062495604.py:14(cpu_heavy_task)

171796964 4.717 2.745e-08 4.717 2.745e-08 1062495604.py:31(simulate_tiny_op)

1 3.848 3.848 3.848 3.848 1062495604.py:22(memory_heavy_string_task)

34552942 1.91 5.527e-08 1.91 5.527e-08 ~:0()

34552942 1.836 5.313e-08 1.836 5.313e-08 ~:0()

34552942 1.305 3.778e-08 1.305 3.778e-08 ~:0()

1 0.02127 0.02127 31.09 31.09 :1()

4 0.0001764 4.409e-05 0.0001764 4.409e-05 socket.py:626(send)

10 0.000123 1.23e-05 0.0004568 4.568e-05 iostream.py:655(write)

4 4.594e-05 1.148e-05 0.0002735 6.838e-05 iostream.py:259(schedule)

...

...

... Step 3: The Fix

Of course, tools like cprofiler and snakeviz don’t tell you how to sort out your performance issues, but now that I knew exactly where the problems were, I could apply targeted fixes.

# final_showcase_fixed_v2.py

import time

import math

import numpy as np

# ===================================================================

CPU_ITERATIONS = 34552942

STRING_ITERATIONS = 46658100

LOOP_ITERATIONS = 171796964

# ===================================================================

# --- Fix 1: Vectorization for the CPU-Bound Task ---

def cpu_heavy_task_fixed(iterations):

"""

Fixed by using NumPy to perform the complex math on an entire array

at once, in highly optimized C code instead of a Python loop.

"""

print(" -> Running CPU-bound task...")

# Create an array of numbers from 0 to iterations-1

i = np.arange(iterations, dtype=np.float64)

# The same calculation, but vectorized, is orders of magnitude faster

result_array = np.sin(i) * np.cos(i) + np.sqrt(i)

return np.sum(result_array)

# --- Fix 2: Efficient String Joining ---

def memory_heavy_string_task_fixed(iterations):

"""

Fixed by using a list comprehension and a single, efficient ''.join() call.

This avoids creating millions of intermediate string objects.

"""

print(" -> Running Memory/String-bound task...")

chunk = "report_item_abcdefg_123456789_"

# A list comprehension is fast and memory-efficient

parts = [f"|{chunk}{i}" for i in range(iterations)]

return "".join(parts)

# --- Fix 3: Eliminating the "Thousand Cuts" Loop ---

def iteration_heavy_task_fixed(iterations):

"""

Fixed by recognizing the task can be a no-op or a bulk operation.

In a real-world scenario, you would find a way to avoid the loop entirely.

Here, we demonstrate the fix by simply removing the pointless loop.

The goal is to show the cost of the loop itself was the problem.

"""

print(" -> Running Iteration-bound task...")

# The fix is to find a bulk operation or eliminate the need for the loop.

# Since the original function did nothing, the fix is to do nothing, but faster.

return "OK"

# --- Main Orchestrator ---

def run_all_systems():

"""

The main orchestrator now calls the FAST versions of the tasks.

"""

print("--- Starting FINAL FAST Balanced Showcase ---")

cpu_result = cpu_heavy_task_fixed(iterations=CPU_ITERATIONS)

string_result = memory_heavy_string_task_fixed(iterations=STRING_ITERATIONS)

iteration_result = iteration_heavy_task_fixed(iterations=LOOP_ITERATIONS)

print("--- FINAL FAST Balanced Showcase Finished ---")Now we can rerun the cprofiler on our updated code.

import cProfile, pstats, io

pr = cProfile.Profile()

pr.enable()

# Run the function you want to profile

run_all_systems()

pr.disable()

# Dump stats to a string and print the top 10 by cumulative time

s = io.StringIO()

ps = pstats.Stats(pr, stream=s).sort_stats("cumtime")

ps.print_stats(10)

print(s.getvalue())

#

# start of output

#

--- Starting FINAL FAST Balanced Showcase ---

-> Running CPU-bound task...

-> Running Memory/String-bound task...

-> Running Iteration-bound task...

--- FINAL FAST Balanced Showcase Finished ---

197 function calls in 6.063 seconds

Ordered by: cumulative time

List reduced from 52 to 10 due to restriction <10>

ncalls tottime percall cumtime percall filename:lineno(function)

2 0.000 0.000 6.063 3.031 /home/tom/.local/lib/python3.10/site-packages/IPython/core/interactiveshell.py:3541(run_code)

2 0.000 0.000 6.063 3.031 {built-in method builtins.exec}

1 0.002 0.002 6.063 6.063 /tmp/ipykernel_173802/1803406806.py:1()

1 0.402 0.402 6.061 6.061 /tmp/ipykernel_173802/3782967348.py:52(run_all_systems)

1 0.000 0.000 5.152 5.152 /tmp/ipykernel_173802/3782967348.py:27(memory_heavy_string_task_fixed)

1 4.135 4.135 4.135 4.135 /tmp/ipykernel_173802/3782967348.py:35()

1 1.017 1.017 1.017 1.017 {method 'join' of 'str' objects}

1 0.446 0.446 0.505 0.505 /tmp/ipykernel_173802/3782967348.py:14(cpu_heavy_task_fixed)

1 0.045 0.045 0.045 0.045 {built-in method numpy.arange}

1 0.000 0.000 0.014 0.014 <__array_function__ internals>:177(sum) That’s a fantastic result that demonstrates the power of profiling. We spent our effort on the parts of the code that mattered. To be thorough, I also ran snakeviz on the fixed script.

%%snakeviz

run_all_systems()

The most notable change is the reduction in total runtime, from approximately 30 seconds to approximately 6 seconds. This is a 5x speedup, achieved by addressing the three main bottlenecks that were visible in the “before” profile.

Let’s look at each one individually.

1. The iteration_heavy_task

Before (The Problem)

In the first image, the large bar on the left, iteration_heavy_task, is the single biggest bottleneck, consuming 14.3 seconds.

- Why was it slow? This task was a classic “death by a thousand cuts.” The function simulate_tiny_op did almost nothing, but it was called millions of times from inside a pure Python for loop. The immense overhead of the Python interpreter starting and stopping a function call repeatedly was the entire source of the slowness.

The Fix

The fixed version, iteration_heavy_task_fixed, recognised that the goal could be achieved without the loop. In our showcase, this meant removing the pointless loop entirely. In a real-world application, this would involve finding a single “bulk” operation to replace the iterative one.

After (The Result)

In the second image, the iteration_heavy_task bar is completely gone. It is now so fast that its runtime is a tiny fraction of a second and is invisible on the chart. We successfully eliminated a 14.3-second problem.

2. The cpu_heavy_task

Before (The Problem)

The second major bottleneck, clearly visible as the large orange bar on the right, is cpu_heavy_task, which took 12.9 seconds.

- Why was it slow? Like the iteration task, this function was also limited by the speed of the Python for loop. While the math operations inside were fast, the interpreter had to process each of the millions of calculations individually, which is highly inefficient for numerical tasks.

The Fix

The fix was vectorisation using the NumPy library. Instead of using a Python loop, cpu_heavy_task_fixed created a NumPy array and performed all the mathematical operations (np.sqrt, np.sin, etc.) on the entire array simultaneously. These operations are executed in highly optimised, pre-compiled C code, completely bypassing the slow Python interpreter loop.

After (The Result).

Just like the first bottleneck, the cpu_heavy_task bar has vanished from the “after” diagram. Its runtime was reduced from 12.9 seconds to a few milliseconds.

3. The memory_heavy_string_task

Before (The Problem):

In the first diagram, the memory-heavy_string_task was running, but its runtime was small compared to the other two larger issues, so it was relegated to the small, unlabeled sliver of space at the far right. It was a relatively minor issue.

The Fix

The fix for this task was to replace the inefficient report += “…” string concatenation with a much more efficient method: building a list of all the string parts and then calling “”.join() a single time at the end.

After (The Result)

In the second diagram, we see the result of our success. Having eliminated the two 10+ second bottlenecks, the memory-heavy-string-task-fixed is now the new dominant bottleneck, accounting for 4.34 seconds of the total 5.22-second runtime.

Snakeviz even lets us look inside this fixed function. The new most significant contributor is the orange bar labelled

Summary

This article provides a hands-on guide to identifying and resolving performance issues in Python code, arguing that developers should utilise profiling tools to measure performance instead of relying on intuition or guesswork to pinpoint the source of slowdowns.

I demonstrated a methodical workflow using two key tools:-

- cProfile: Python’s built-in profiler, used to gather detailed data on function calls and execution times.

- snakeviz: A visualisation tool that turns cProfile’s data into an interactive “icicle” chart, making it easy to visually identify which parts of the code are consuming the most time.

The article uses a case study of a deliberately slow script engineered with three distinct and significant bottlenecks:

- An iteration-bound task: A function called millions of times in a loop, showcasing the performance cost of Python’s function call overhead (“death by a thousand cuts”).

- A CPU-bound task: A for loop performing millions of math calculations, highlighting the inefficiency of pure Python for heavy numerical work.

- A memory-bound task: A large string built inefficiently using repeated += concatenation.

By analysing the snakeviz output, I pinpointed these three problems and applied targeted fixes.

- The iteration bottleneck was fixed by eliminating the unnecessary loop.

- The CPU bottleneck was resolved with vectorisation using NumPy, which executes mathematical operations in fast, compiled C code.

- The memory bottleneck was fixed by appending string parts to a list and using a single, efficient “”.join() call.

These fixes resulted in a dramatic speedup, reducing the script’s runtime from over 30 seconds to just over 6 seconds. I concluded by demonstrating that, even after major issues are resolved, the profiler can be used again to identify new, smaller bottlenecks, illustrating that performance tuning is an iterative process guided by measurement.

Source link

Add comment